Main menu

Outside Fashion

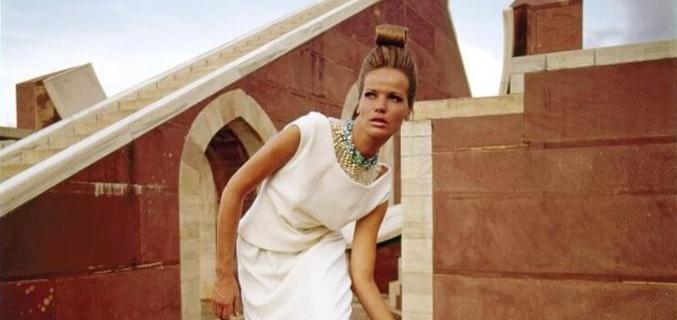

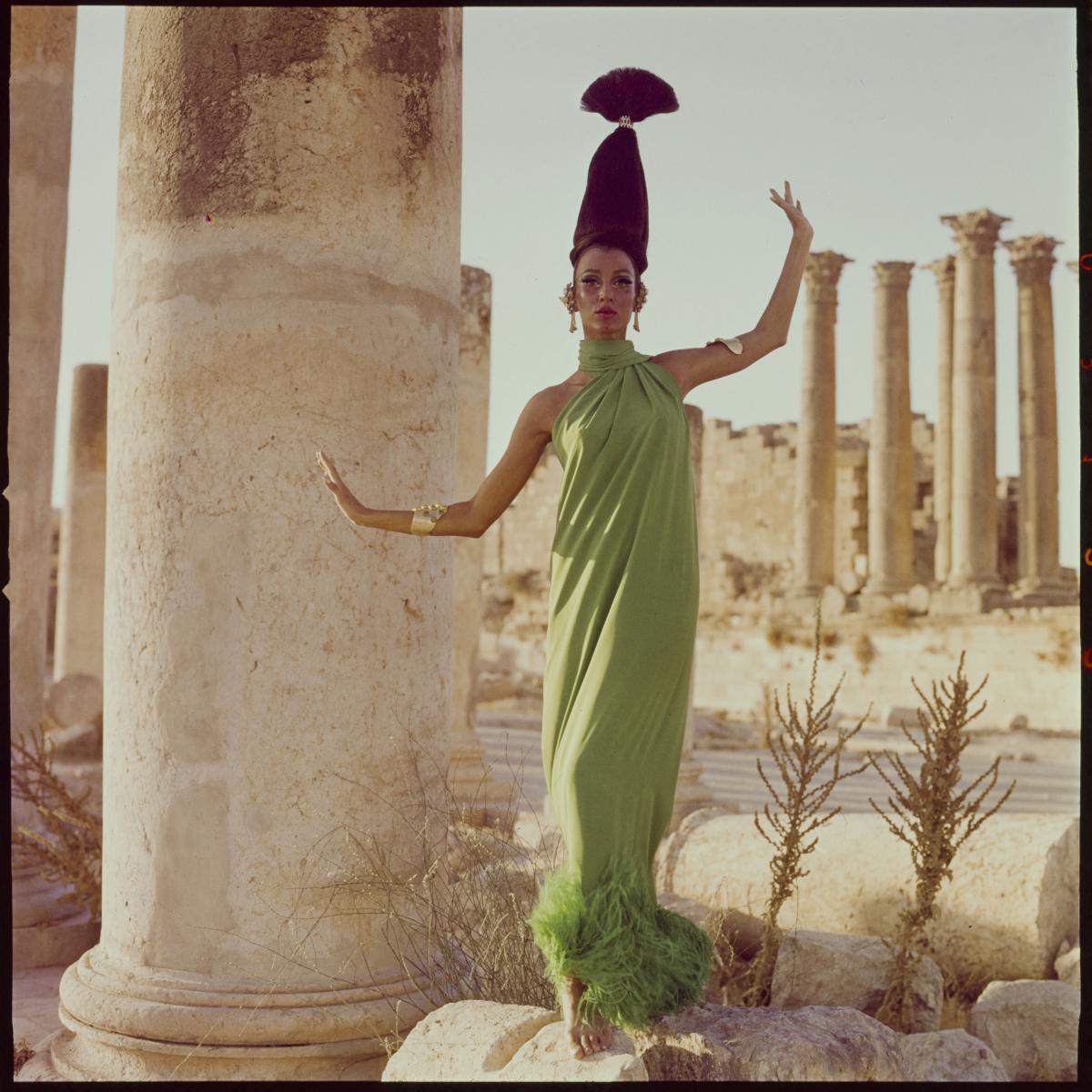

Modèle Veruschka, robe Givenchy pour Adele Simpson, Jantar Mantar, Jaipur, Inde, 1964. © Henry Clarke / Galliera / Roger-Viollet

Fashion photography, from the studio to exotic lands (1900-1969)

07.12.2019 — 08.03.2020

Extra muros

For the first time, unpublished photographs from our collections are being exhibited in Amsterdam. "Outside Fashion" traces the history and evolution of fashion photography from 1900 to 1969, including the transition from studio to outdoor shoots.

Born in portraitist studios at the end of the 18th century, fashion photography started at the turn of the 20th century started to represent the exterior world in order to better anchor the garments in reality. If the studio searched in the beginning to recreate the illusion of the outdoors by methods of illusion and sophisticated lighting, the industry understood very quickly that there was an interest in putting the models in natural settings, proper to the clothes that they were wearing. Racecourses, the beaches of Deauville, and walks in the woods all constituted ideal locations to show the latest collections. Fashion made its first steps outside.

In the middle of the 1930s, fashion reporting brings a new breath to fashion, upsetting the confined codes of the studio. This aesthetic becomes the new vision that revives the genre of fashion photography. Jean Moral’s work with Harper’s Bazaar is one of the most remarkable examples.

After the Second World War, Paris is the background of an haute couture industry all at once reborn and on the decline. The capital is the décor of settings that have since become iconic and always copied. In parallel, tourism turns itself towards the sun, and the first voyages by Boeing drag the world towards destinations farther and farther away. The fashion photographs of Henry Clarke for Vogue contain exotic colors.

Outdoor fashion photography defines itself as a genre apart from the rest. From gardens made of painted backgrounds to Indian palaces, fashion photography did not cease to open up the world. This exposition proposes to retrace this history.

Artifice

Talbot, the singer Nelly Martyl in a leopard coat Max, Leroy and Schmid furs, circa 1910.

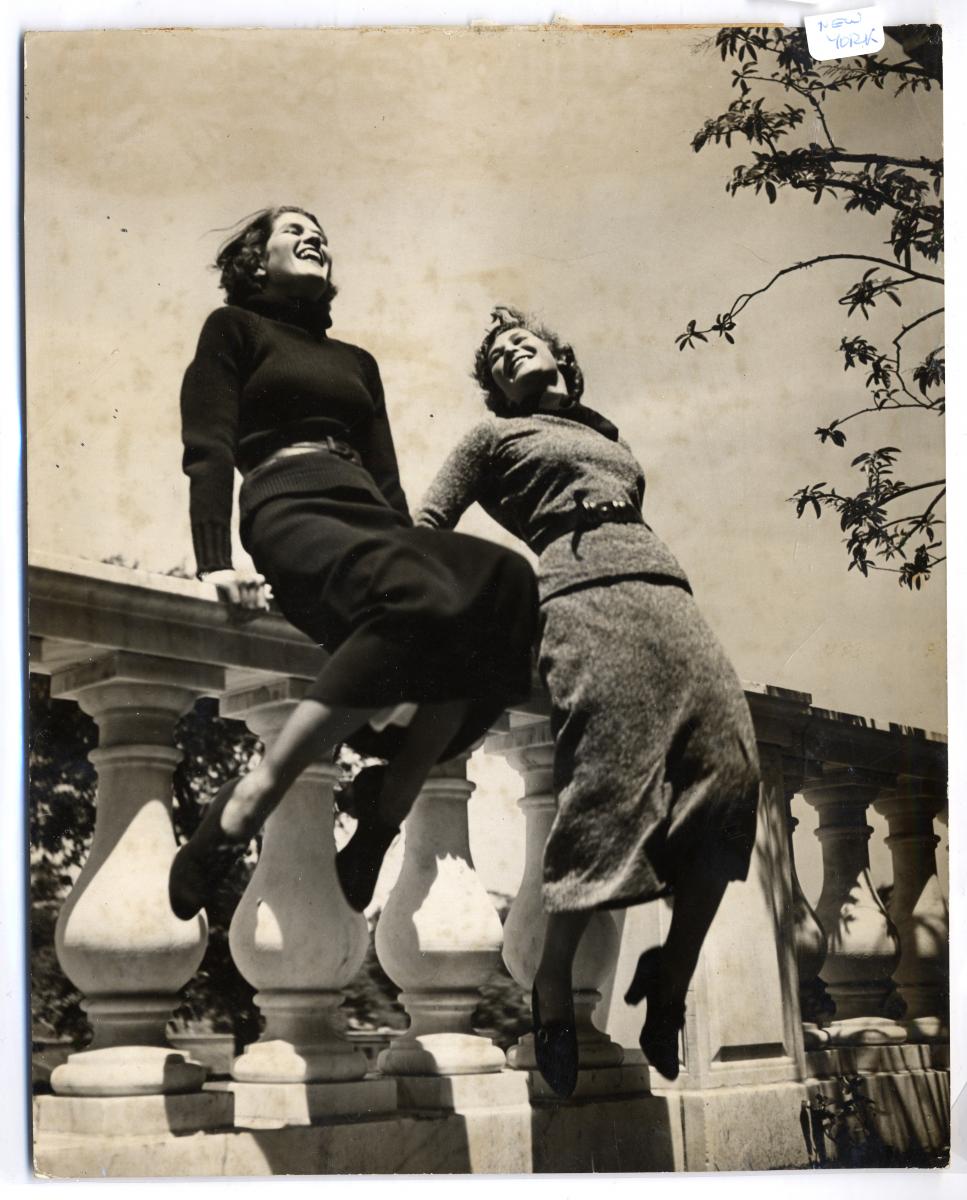

Printed in the Revues de la mode at the end of the 19th century, photography competed with illustration because of its realism. The finesse of prints and engraving permitted the magazine to show details, translating the subtlety of materials and textiles characteristic of fashion before 1914. Fashion photography therefore flourished in the studios of portraitists, taking back conventions of décor, accessories, and posing. The use of painted backgrounds evoking the outdoors used by engravers of the 19th century and benefits in the realism brought to fashion by photography. The painted backgrounds also echo the represented outfits: parks with bare trees for fur stoles, flowering gardens for afternoon outfits. In featuring a fake, outside world, these images from before the war sketch the line in between fashion of an era and its environment. But they also speak equally of the narrowmindedness of the studio. In the 1920s and 30s, the studio is still the center of fashion photography. It abandons the painted backgrounds for sets straight out of the cinema. With Egidio Scaioni (1894-1966) or Dorvyne, some accessories, fake grass and tree branches, and some painted stones on a wall become a banister, evoking a townhouse, or even the deck of a boat, a port, or a beach. Lights recreate the daylight, at its height, dazzling, silhouetted. Photographic backgrounds are projected in the background so that all the decors are possible. A faraway look, outside the field, opened some of the closed space within the studio, with a possibility of fictions, the start of a story to tell. The bird’s eye view widens the gaze, detaching the young women from the ground and placing them within infinite skies. One lets modernity take charge of these photographic settings. The women are dynamic, independent, and active. It is time to leave the studio.

First Steps Outside

Séeberger Frères, the Dorys model for Agnès, at the races at Longchamp, 1933.

At the end of the 19th century, outfits seen at the races were illustrated in fashion publications. Photographs of elegant women and of professional models appear in Femina, from 1902-1903, and in L’Illustration, near the end of the early 1900s. More than for the races, one went to Longchamp to see new outfits. Fashion journals echoed them. Sometimes the image made the cover: the apparition of models starting new trends was in itself an event. Photographs taken at the races were their own genre. Taken outside, these photographs put the models in real situations. The blurred background draws the viewer’s attention to the outfits, in a concern for commercial efficiency. Outside the studio, photography tries to capture movement. Paul Poiret is one of the first to have presented his collections in the gardens of his couture house. The perceptible variations of daylight give a naturalist dimension to the images, showing them in diptych, in front, and in profile, suggesting the possible movements of the models’ bodies. By their documentary character, these first photographs anchor haute couture models in reality, convincing the reader that they were receiving the most updated fashions. Some themes dominate the reflection of 1930s modernity. The fashion of the day is in tandem with the new, feminine activities, and the high bourgeoisie leave for the streets. Outside of urban occupations, the time period is concerned with voyages, physical activity, and sunbathing: the liberation of the body which logically accompanies fashion photography to the outdoors. If a sketch of movement is drawn, the stage dressing is visible, the models frozen in an illusion of spontaneity.

Jean Moral (1906-2001)

Jean Moral, John Wanamaker and Lord & Taylor ensembles, New York, 1935.

At the start of the 1930s, technical evolutions turn photography on its head. The creation of small cameras, such as the Leica and the Contax, becomes useful to reporting photographers and illustrators. The Rolleiflex, a medium-sized camera that was easy to use, brought a larger mobility and a larger rapidity to fashion photography, permitting photographers to take photographs of models in almost any situation. These new fashion images appeared in magazines for essentially commercial reasons. In the 1930s, Carmel Snow, chief editor of Harper’s Bazaar, needed to promote American sportswear to women who were more and more active. Martin Munkacsi, in The United States, and Jean Moral, in France, were also engaged in this objective. Belonging to the current French vision, while reporting, Jean Moral photographed easy to wear fashions in Paris: wool suits or printed day dresses. Starting in 1934, he infused the pages of Harper’s Bazaar with an air of freedom and an unpolished freshness. The smiling models resemble women of their time. The naturalism of the photographer reinforces their spontaneity. Their gazes, often turned toward the camera, tell the proximity of the models to the photographer, and similarly, permit the reader to identify with the models. A big traveler and athlete, Jean Moral is distinguished by his dynamic approach to his subjects, his photos often taken from a point of view slightly above his models with a long focal point. The bodies of women are living, active, inscribed in modernity. In 1940, as Harper’s Bazaar supports Parisian haute couture, Moral shoots the suits of Molyneux or of Lucien Lelong in a capital that is preparing itself for war. Elegant in all circumstances, the Parisienne is active in a city in touch with reality.

Paris

Henry Clarke, Jacques Fath coat, Paris, 1949.

The post-war years accentuated the predominance of Paris in the matter of fashion; they signaled the return of opulence and luxury. In the photographs of Henry Clarke and Willy Maywald, the capital is the ideal setting in which to shoot haute couture. The suits abandoned their salons and left for the streets, traversing the Place des Victoires or the Place Vendôme, descending on the banks of the Seine. At the same time, the popular image of Paris benefits from an imagery which validates the authenticity of its places. In the 1960s, Peter Knapp brought fashion into a new dimension in photographing, at night, an ensemble by Courrèges on the Champs Élysées. More than outside or the open air, it is the street that henceforth defines fashion photography, in contrast to the closed, artificial atmosphere of a studio. The inscription of the model to the urban flux translates the way in which fashion photography integrates street photography at the heart of its own commercial and aesthetic system. Beyond the staging of fashion in an urban setting, no matter how contemporary it seems, the innovative idea is to take resources from reality. To accompany the birth of a young and democratic ready-to-wear industry, David Bailey and William Klein changed points of view. Using small formats, working like reporters, they played with large angles and long focal lengths in order to place their models into an effervescent city. Jean Shrimpton, shot by David Bailey for Vogue, in 1962, is emblematic of this ideal meeting in the history of fashion photography, between the youth of a fashion model, the audacity of a fashion photographer, and the energy of the city.

Exoticisms

Henry Clarke, Pierre Cardin dress, Jordan, 1965.

At the start of the 1950s, fashion staged in faraway countries became a separate category in fashion magazines. Far from being an excuse for new settings, this new genre was in development since the birth of international tourism. Summer dresses and swimsuits were therefore photographed on the Côte d’Azur or in the South of Europe. In 1958, the Boeing 707 announced the era of jets, which in reducing the time of voyage and in lowering the prices, permitted people to go to places that were previously inaccessible. Starting in the 1960s, exotic voyages multiplied, as did the fashion press, finding the perfect ally in color, photographers left to conquer places that were at once geographical and aesthetic. The December 1964 issue of the American edition of Vogue marked a turning point in fashion photography. Diana Vreeland, editor in chief since 1963, had the idea to send Henry Clarke, a fashion editor, an assistant, a hairdresser, and two models to India. The success of this voyage consisted of 27 color photographs, permitting Vogue to use these photographs two times per year. Until 1969, Henry Clarke also went to Brazil, Syria, Jordan, Ceylan (now known as Sri Lanka), Turkey, Mexico, Spain, Iran, and again to India, for these exceptional fashion voyages. India and Turkey fed the collective imagination. Indian and Mexican temples, Syrian ruins, the Indian palaces of the Maharajahs, are vestiges of fallen civilizations and possess a very strong mythological dimension. The models and the clothing, a “resort” fashion, coming mainly from American ready-to-wear fashion, reveal this exoticism. In mixing the East and the West, exoticism and commercial interests, these images, strongly anchored in the 1960s, make up a unique moment in the history of fashion photography.

Produced from the photographic collections of the Palais Galliera, the City of Paris Fashion Museum, this exhibition is supported by the French Institute of the Netherlands and the French Embassy in the Netherlands.

Curator: Sylvie Lécallier, in charge of the photographic collections of the Palais Galliera

- Extra muros exhibition:

- Huis Marseille, Museum for Photography (Amsterdam, Pays-Bas)

-

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

- "Outside Fashion", Huis Marseille, 2019-2020 © Eddo Hartmann

image 1/19

Visitor information

- Price:

€ 9,–: full price

€ 4,50: students / senior citizens (65+) / groups of at least 8 / CJP / Rembrandtpas

Free admission: children ages 17 and under / Museumcard / I Amsterdam City Card / Stadspas / ICOM- Ticket website:

- Ticket access

- Information:

Huis Marseille, Museum for Photography

Keizersgracht 401

1016 EK Amsterdam

Pays-Bas

The Netherlands

+ d'information :

>> www.huismarseille.nl

Contact Presse :

Benjamin van Gaalen

T: +31 (0) 20 531 89 87

E: benjaminvangaalen@huismarseille.nl