Main menu

Duchess of Galliera

'[...] she lived only for charity and in it found her only true happiness.' — L'Illustration, 15 December 1888

Praised for her philanthropic actions, considered warm-hearted, with a generous and charitable soul, the Duchess of Galliera led a remarkable life and was dedicated to beauty and altruism.

Quick access to chapter:

Early life and family

Go to top pageMarie Brignole-Sale was born in Genoa on 5 April 1811, into a patrician family that had given its city doges, senators, ambassadors and poets. An enlightened education was further enhanced by regular trips with her father on his diplomatic missions: Marquis Antoine de Brignole-Sale was made Prefect of the Ligurian Republic by Napoleon Bonaparte, going on to become the Sardinian ambassador to France, where he was held in high regard by King Louis-Philippe. This appointment meant that Marie was, so to speak, raised at the Tuileries palace with Louis-Philippe's children, to whom she remained deeply attached.

Slim, blonde, blue-eyed and fine-featured, this highly intelligent, multilingual young woman married Marquis Raphaël de Ferrari in 1828. The main builder of railways in Upper Italy and developer of the Paris-Lyon-Méditerranean line, he was joint founder, with the Pereire brothers, of the Crédit Immobilier bank; he also took part in the construction of the Suez Canal. The transformation of Paris instigated by Baron Haussmann provided the opportunity for numerous, highly profitable real-estate transactions.

The couple had three children, Livia (1828–1829), Andrea (1831–1847) and Philippe (1850–1917). The sudden death of Andrea in 1847 – he had been brought up with Antoine d’Orléans, Duc de Montpensier, the younger son of King Louis-Philippe – bound the two families even more closely together, and Marie became immensely fond of Antoine. Philippe, the youngest of her children, was a brilliant student whose passion for postage stamps led to one of the world's largest stamp collections. He was, also, an eccentric driven by a spirit of revolt against his family.

The Gallieras: the wealthiest people in France

Go to top pageIn 1837, Marie and her husband acquired the Galliera estate on the river Reno, in Emilia-Romagna, Italy. On 14 May 1813 Napoleon had made the estate a duchy for Mademoiselle de Beauharnais, his adoptive granddaughter. The title reverted to the Church after Napoleon's defeat in 1815 and when Pope Gregory XVI bestowed it on the Ferraris in 1838, Marie Brignole-Sale, Marquise de Ferrari, decided to be known as the Duchesse de Galliera.

Writers of the time refer to the couple as the richest people in the Empire, able to purchase mansions and palaces at will. In 1852 the duke and duchess bought the Hôtel Matignon, the Duc de Montpensier's Paris town house, when the latter was forced to sell: the revolution of 1848 had brought the Orléans family to the brink of bankruptcy.

It is said that the Duchesse de Galliera's new town house on Rue de Varenne had a domestic staff of 200. She made it a focal point of the city's political, intellectual and social life, drawing into its orbit figures like the Pereire brothers, the Duc de Morny, the Duc de Broglie and Prosper Mérimée.

Ever faithful to their Italian roots, the Gallieras bought the Luciedo estate in Piedmont, and that same year were made Prince and Princess of Luciedo by Victor-Emmanuel II of Savoy.

This ongoing enrichment and succession of purchases in Italy and France was brought to an abrupt halt by Raphaël's death in Genoa on 22 November 1876. When Philippe, their only son, refused the family heritage outright, the duchess succeeded in having the title passed on to Antoine d’Orléans, whom she loved like a son.

The philanthropist

Go to top pageNow 65 and a widow spurned by her son, the Duchesse de Galliera found herself the possessor of an immense fortune of 225 million gold francs, which she then began devoting to charitable works. She founded the Ferrari Hospice for the aged in Clamart and an orphanage in Meudon. Designed by architect Paul-René-Léon Ginain, the hospice drew unfavourable criticism for its luxurious appearance, to which its founder replied, 'I am a child of my country. In Italy we love palaces: they are to be found everywhere and I own several. Is it not just that in France the poor should have their own?' (in Magasin pittoresque, 1889, p. 32.)

With a gift of one million gold francs she also helped create Emile Boutmy's Ecole Libre des Sciences Politiques, now the famous 'Sciences Po'.

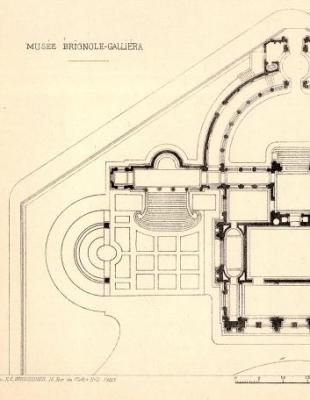

Very much a woman of her time – a century that saw museums and galleries springing up all over Europe – the duchess decided to found a museum for her Paris collection, a palace to be built on a plot of land her husband had bought. Her aims were firm and carefully thought through: she signed her acceptance of the plans on 10 April 1878, five days before officially submitting her proposal to the authorities. On 11 July the Paris municipal council gave its assent to the donation.

Begun by her ancestors in 1623 – when Van Dyck painted a family portrait for them – and constantly added to, the art collection was distinguished and varied, including Flemish, Spanish and Italian paintings, 18th-century French furniture, and clocks and other items from the Sèvres and Gobelins manufactories. All the great names were represented.

However, the project was jeopardised when the duchess's personal history clashed with that of France: outraged by the law of 1883 concerning the expulsion from France of previously ruling royal and imperial families and by the law of 14 August 1884 making the Comte de Paris ineligible for the presidency, this official benefactor of Paris decided to retaliate in her own way. In a handwritten will dated 7 October 1884, she withdrew the bequest of her collection to France in favour of the Palazzo Rosso in Genoa. Thus she disinherited Paris, the city where she was most at home. Nonetheless, the building of the Palais Galliera went ahead and when it was completed she put it at the disposition of the City of Paris.

Marie Brignole-Sale, Duchesse de Galliera, died in Paris on 9 December 1888, aged 77.