Main menu

18th-Century Dress Department

This is one of the world's leading collections of eighteenth-century dresses. Home to some 1,600 items, it comprises men's and women's garments dating from the late 17th century to the year 1800, together with children's wear and theatre costumes; these are an interesting reflection of both the fashions and the textile industry of the time.

The 900-plus male items represent more than half the department's holdings, with such rare and elaborate pieces as a 1670s jerkin and court clothes of silver brocade or velvet embroidered with gilded silver thread – not to mention 350 waistcoats, whose quantity reflects an Ancien Régime fashion craze. The women's collection includes a host of dresses à la française and à l’anglaise, as well as caracos and bodices. There are reminders of France's royal past, too: two suits and a chemise worn by the Dauphin, the future Louis XVII, together with a bodice said to have belonged to Marie Antoinette. They are shown here both for their historical interest and as indicators of the fashions of the period.

The exuberance of the early 18th century can be seen in the men's long basques, cut from dark fabrics with thick embroidery, and for women, large-patterned dresses with pleated backs and the skirts puffed out with paniers. Around 1750–1755 the dresses were made of silk, with long, sinuous trimmings testifying to the period's rococo taste. During the reign of Louis XVI the male silhouette slimmed down and clothes were made of velvet or taffeta, either plain or with little patterns of delicate floral embroidery. Waistcoats were light-coloured and picturesquely embroidered. The feminine wardrobe became more varied, the dress à la française with its wide, pleated back alternating with the dress à l'anglaise, whose narrow waist highlighted feminine curves. At the end of the century, close-fitting coats, straight waistcoats and tunic dresses of cotton muslin or lawn signaled a new relationship with the body: the natural replaced the artificial.

Fashion in 18th-century Paris saw many radical changes. The varied range of clothing was illustrated by the fashion press, which had begun to publish periodically; new, alluring engravings – printed cottons, white cotton muslin, silk or silk/wool jersey – reflected technical advances and guaranteed the wearer unheard-of comfort and an aura of modernity. One iconic figure stands out in this century when modern fashion was born: the marchande de mode, or dressmaker/milliner, whose most famous representative was Rose Bertin, Marie-Antoinette's 'minister of fashion'. Bertin captured royal and princely clienteles not only at Versailles, but in other European courts as well. With her arrival, the marchande de mode no longer settled merely for decorating dresses and selling lace, feathers, gauze, hats and fans; she imposed on her customers the need for a knowledgeable guide in the supreme realm of fashion.

-

Gown known as 'Robe volante'

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

Sack-back gown

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

Mantle and shoulder cape of a knight of the Order of the Holy Spirit

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

Chemise worn by Louis XVII

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

Coat and trousers worn by Louis XVII

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

Coat, waistcoat and trousers worn by Louis XVII

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

Bodice said to have belonged to Marie Antoinette

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

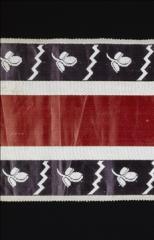

Ribbon said to have belonged to Madame Adelaïde

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

Dress coat bearing the livery of the King of France

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

Waistcoat worn by Claude Lamoral II

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

Casaquin

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

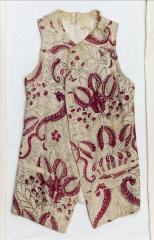

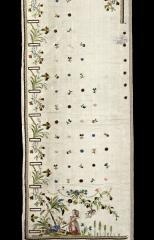

Man's Waistcoat

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

Man's coat of Saint François de Sales

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

'The People's representative' coat

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

Man's Waistcoat

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

Man's dressing gown

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

'Rinaldo & Armida' waistcoat

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

'Voltaire & Rousseau' waistcoat

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

Harlequin costume

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

'Carmagnole' jacket

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre

-

Man's three-part ensemble

Voir la fiche de l'oeuvre